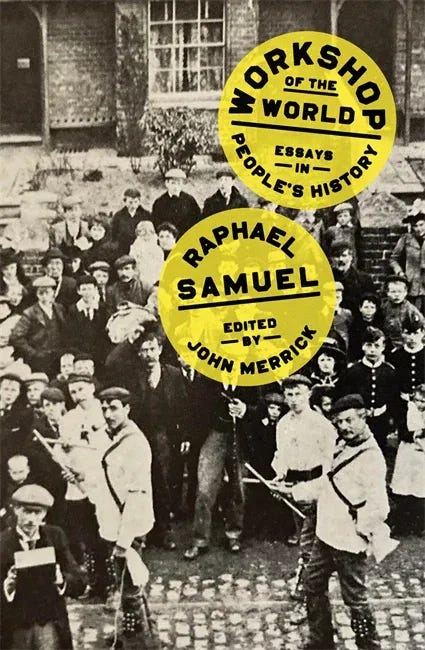

The collection of Raphael Samuel’s essays I edited has now been out for 8 months. In that time it’s garnered far more attention than I could have hoped for, which is a nice bonus after all of the work I put into it over several years. It was a big project, done from enthusiasm with no hope of financial reward. I had wanted to get a version of my introduction to the volume extracted, but that wasn’t to be, for various reasons. Instead, I’m publishing it in full below.

The essay itself was intended as much as much as an introduction to Raph’s life and work as it is to the essays in the volume. There have been some wonderfully kind things said about it, not least from his widow, Alison Light, and his former students like Sally Alexander, without whom I wouldn’t have been able to do any of this. I hope it whets your appetite for Raph and his work (if it does, please consider buying the book; if enough people purchase it, I might even have a case for a second volume of essays).

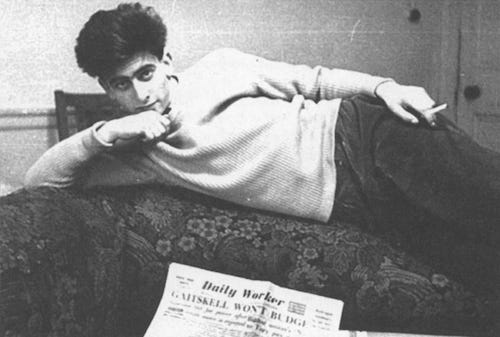

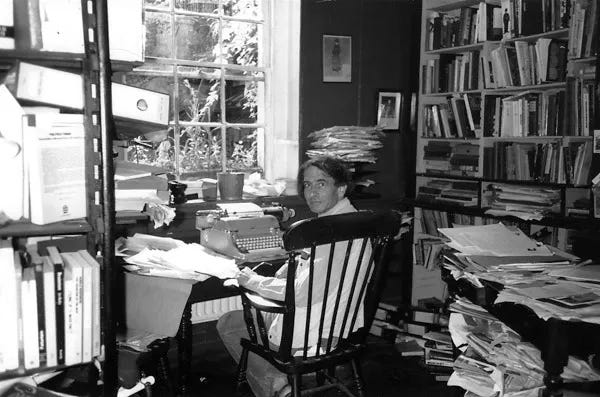

There is a video of Raphael Samuel, one of the most original of that remarkable generation of historians within the British left in the late twentieth century, sitting in a characteristically book-filled room, his unruly mop of thick black hair pushed across the crown of his head, discussing the drama of British history. The recording, short at only a minute and a half, is now on YouTube and is one of only a handful of surviving recordings of that famously captivating lecturer.

‘If you want to understand Britain between the two wars,’ he says, his eyes bright with the enthusiasm and attentiveness that marked the ‘rare capacity to listen’ that his widow Alison Light has suggested made him so charismatic, then ‘something like the ballroom dancing craze of the 1920s … or the rambling craze, or the cycling craze’ is equally as important as the major political shifts of those decisive decades. By taking seriously and understanding such fleeting national enthusiasms – everything from sunbathing to cycling – as the raw material of history, not only can we understand the changing relationship between people and nature or work, but perhaps we can also see something new in the drama of history. History from below, he says, is ‘as least as dramatic … as history from above’. ‘I absolutely refuse the idea that the Treaty of Utrecht, interesting though it is, … represents as it were the high point of national drama.’

Such was his thoroughly democratic historical vision. More than that, history, according to Samuel, was far too important to be left to professional historians alone. Theatres of Memory, the only sole-authored book he published in his lifetime, is a thrilling and often labyrinthine text that evokes the occult Renaissance memory theatres of its title. It explores those sources of unofficial memory that for most people constitute their historical consciousness. Historians, who spend their lives writing specialised texts, often read by none but the accredited few, have at best a walk-on part; the book’s joy comes as much from its following unexpected detours and new connections as from its central argument.

It is also, as Bill Schwarz remarks in his preface to the second edition, a self-consciously open text. Samuel, Schwarz writes, ‘works to minimize, at every point, the gap between the author and the printed word and between the printed word and the reader.’[i] His vast erudition and the depth of his historical understanding was not used to build new professionalised historical structures, but to tear them down. If there was an animating spirit of his work it was a deep faith in the ability, and necessity, of ordinary people to become the custodians of their own histories. His mission was nothing less than the democratisation of historical knowledge.

‘History,’ Samuel writes, ‘in the hands of the professional historian, is apt to present itself as an esoteric form of knowledge.’ It is a discipline that, with all its Rankean claims to scientific specialism, and in the hands of its ensconced elite, forgets as much as it remembers. It serves to enclose knowledge behind thick walls of academic apparatus. The professional’s view of knowledge is a hierarchical one. Knowledge flows downward from its practitioners to, if they are lucky, the inert public at large. And what counts as history, and who counts as a historian, is radically curtailed.

Samuel’s aim in Theatres of Memory is to disrupt this hierarchy, and to take seriously such disparaged cultural forms as historical re-enactment societies, the boom in period productions on stage and screen, and such miscellany of the heritage industry as Crabtree & Evelyn. What, he asks, can the late-1980s mania for bare brickwork interiors tell us about how contemporary society sees its own past? How can we read popular culture – David Lynch’s Elephant Man; Christine Edzard’s Little Dorrit – as a crucible of popular memory? And just what does each say about the popular articulations of the past in the present?

There is, however, an obvious tension here. History may be in thrall to all manner of arcane questions and occult knowledges – the ‘cabbala of acronyms, abbreviations and signs’ that typify the discipline’s professionalisation and signal to the lay reader its off-putting specialism, along with its ‘dense thickets of footnotage’ and fetishisation of archive-based research – but these are occult methods at which Samuel himself was adept.[ii] Samuel may have sought to democratise and de-professionalise the production of historical knowledge, but as the essays collected in this volume demonstrate, the depth and breadth of his own historical writing should not be forgotten either.

Born towards the end of 1934 in London and brought up first in Hampstead Garden Suburb, and later in nearby Parliament Hill, Raphael Samuel was a committed member of the Communist Party of Great Britain from a young age. His mother, Minna Nerenstein, later Keal, joined the Party (as it was universally known to its activists) in 1939, the same year that Samuel’s progressive north London school was evacuated to Bedfordshire. Minna was one of twelve of Raphael’s close relatives who were in the Party, and many of his weekends away from school were spent with his mother in Slough, where she worked in an aircraft factory, or assisted with Party work. Otherwise, he could be found in Belsize Park with his aunt and uncle, Miriam and Chimen Abramsky, the latter a renowned Judaic scholar and historian of socialism with an encyclopaedic knowledge of Marxism.

His early life was, he later reflected, ‘an intensely communist one’.[iii] ‘To be a Communist’, he wrote in a series of essays posthumously gathered together into the book The Lost World of British Communism, ‘was to have a complete social identity, one which transcended the limits of class, gender and nationality.’[iv] It was a ‘crusading order’ as much as a political grouping; ‘the way, the truth, the light’, in which members like Samuel were ‘waging temporal warfare for the sake of a spiritual end’.[v] If this sounds more like an ecclesiastical order than a political party, then that’s partly due to the healthy dose of the religious mixed in, albeit in stridently atheistic tones. As he writes in the essay ‘A Spiritual Elect? Robert Tressell and the Early Socialists’ collected in this volume, socialists had long seen themselves as a ‘people apart’ and a ‘peculiar people’ – a phrase resonant with the echoes of Christian Dissent.[vi] It was, Samuel writes, often a ‘kind of displaced religious longing’ that drew Communists in to the fold, and ‘those who came to socialism in these years embraced it with the rapture of a new-found faith.’[vii]

If Communism provided a faith, as well as a powerful sense of belonging, it was also an apprenticeship in learning. As Samuel evocatively recalls, Party members and fellow travellers alike were a deeply learned bunch, and the Party itself placed great emphasis on intellectual self-improvement. The work required of Party membership was met by the young Ralph (as he was then known, due to the inability of his comrades to pronounce the name Raphael) with such seriousness that, during the war years, he become ‘a kind of juvenile commissar of the family’, maintaining the orthodoxy of their commitment, and even giving a copy of Plekhanov’s In Defence of Materialism to his mother for Christmas 1950. And if Party work gave him a form of belief that stretched beyond the immediate and out into the world at large, it also provided a sense of mission and an intense suspicion of the merely individual. One of the great ‘folk devils’ of the Party was the ‘careerist’, ‘a species being’ he writes ‘of whom I am, to this day, wary’; its hero, the committed and selfless organiser.[viii]

The essays in The Lost World, blending memoir and historical analysis with a literary skill that few other historians have managed, contain many such richly suggestive details. The focus is as much on the passing remark as the flow of narrative. As Alison Light remarks, even the essays’ footnotes speak volumes, bringing together the more conventional historical source material with the quixotic: autobiographies, both published and unpublished, from Party leaders and ordinary members; the amateur poetry of cadre; posters, handbills and other pieces of ephemera; and a plethora of original interviews conducted by Samuel himself with Party veterans.[ix] We hear of Iris Kingston, the unlucky comrade from St Pancras, who in 1926 was reprimanded by London District for questioning the materialist conception of history. Elsewhere, a young and eager Raphael impishly whistles the tune of ‘The Internationale’ on the London Underground to see which passengers might respond. There is, here, a wonderful eye for the telling detail. His essays seem to delight in piling information together into great mounds that could easily, in the hands of a less gifted storyteller, collapse, taking all with it. But Samuel seems to conjure forth whole historical worlds from the mere gathering of information.

At the age of seventeen, Samuel left King Alfred’s School in Hampstead, another progressive institution, to attend Balliol College, Oxford, on a scholarship. Here he read history with Christopher Hill, the historian of the seventeenth century and fellow member of the Communist Party Historians’ Group, which Raphael had joined as a precocious sixteen-year-old under the influence of his uncle. Yet, despite Hill’s mentorship, the atmosphere for the young communist at Oxford was hostile, and Samuel found the intellectual climate of the college cold. As he told Brian Harrison in an interview conducted in the late 1970s, the majority of his time at Oxford was spent, at least initially, ‘as a political activist, as a communist’, helping to revive the moribund Oxford Labour Club as well as organising with the university branch of the CPGB.[x]

After a year’s break in order to do Party work in London, Samuel graduated in the summer of 1956 with a first-class degree, and immediately set his sights on becoming a full-time Communist organiser. Events in Eastern Europe were, however, to intervene. Nikita Khrushchev’s ‘secret speech’ given to the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union took place in late February of that year, and by mid-March the news had begun to trickle through to the British press. By November, the crisis in the Party became more acute again as Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest to crush the Hungarian uprising. These events threw the Party into turmoil, and nearly ten thousand people, Samuel included, left in protest by the end of 1958.[xi]

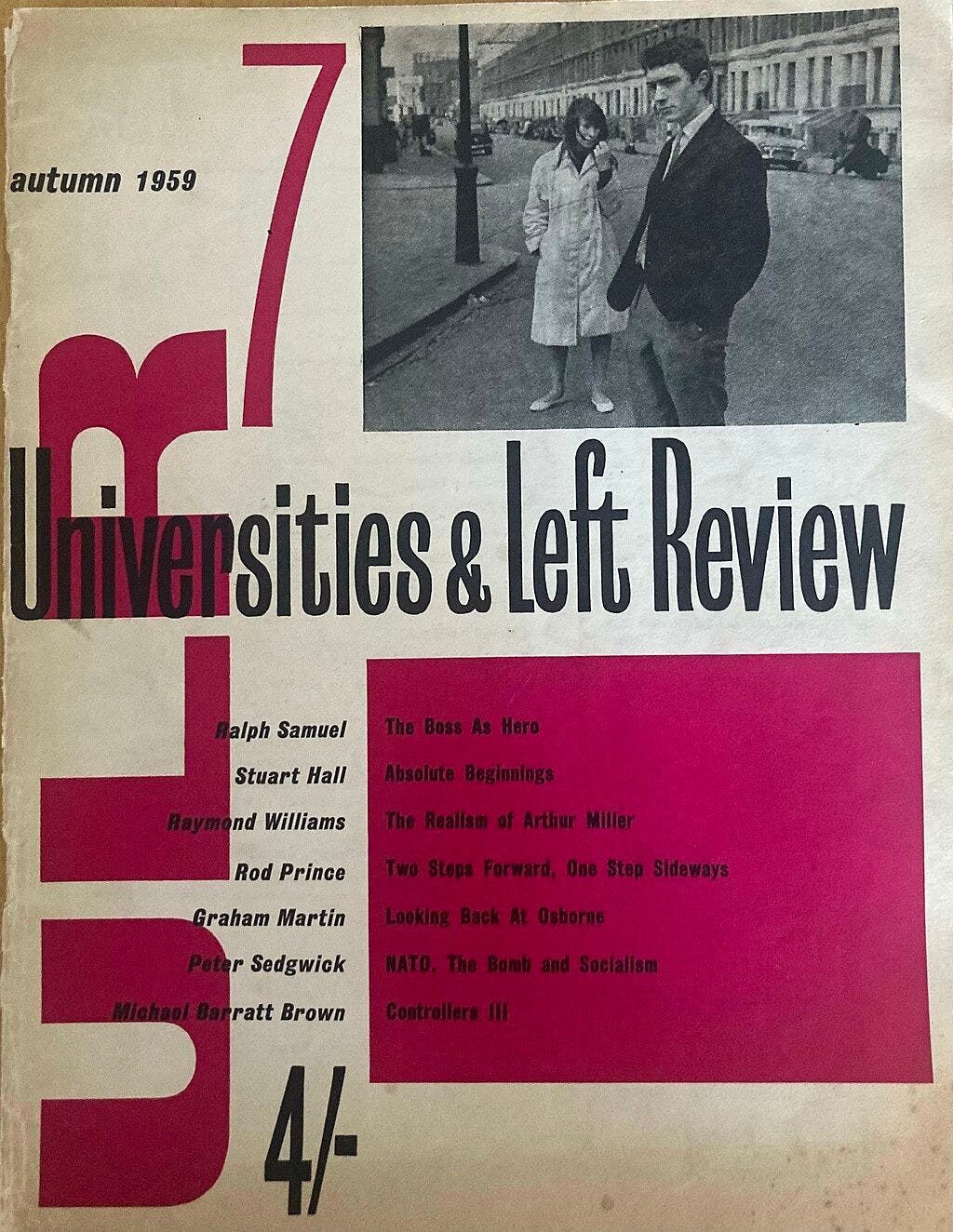

That the events that have come to stand in the annals of the left under the heading ‘1956’ – and which included the Anglo-French imperial debacle in Suez as well as events beyond the Iron Curtain – occasioned no retreat from the political would have surprised those who lived through previous such crises. Rather, a great outpouring of political enthusiasm ensued, a result of which was the birth of the New Left, one of the more creative and consequential political and intellectual movements to emerge in post-war Britain. Barely a month after the events in Hungary reached their tragic nadir, Samuel, along with his friends and comrades from Oxford, Gabriel Pearson, Stuart Hall, and Charles Taylor, founded the magazine Universities and Left Review. Its first issue emerged in spring of 1957, and contained essays by Pearson, Hall, and Taylor, as well as contributions from the artist Peter de Francia, the noted British New Wave filmmaker Lindsay Anderson, the economist Joan Robinson, the historians E. P. Thompson, Eric Hobsbawm, and Isaac Deutscher, and the town planner Graeme Shankland. This heterogenous mix of contributors, blending more conventional socialist essays with cultural criticism, would mark it out from many of the left periodicals that had come before. And, while only running for seven issues, with the last sent to the printers in late 1959, its deep intellectual and political commitment, alongside its engagement with the burgeoning youth culture of the late 1950s and its pioneering design work from future Penguin design director Germano Facetti among others, would mean that its influence stretched far beyond its limited run.

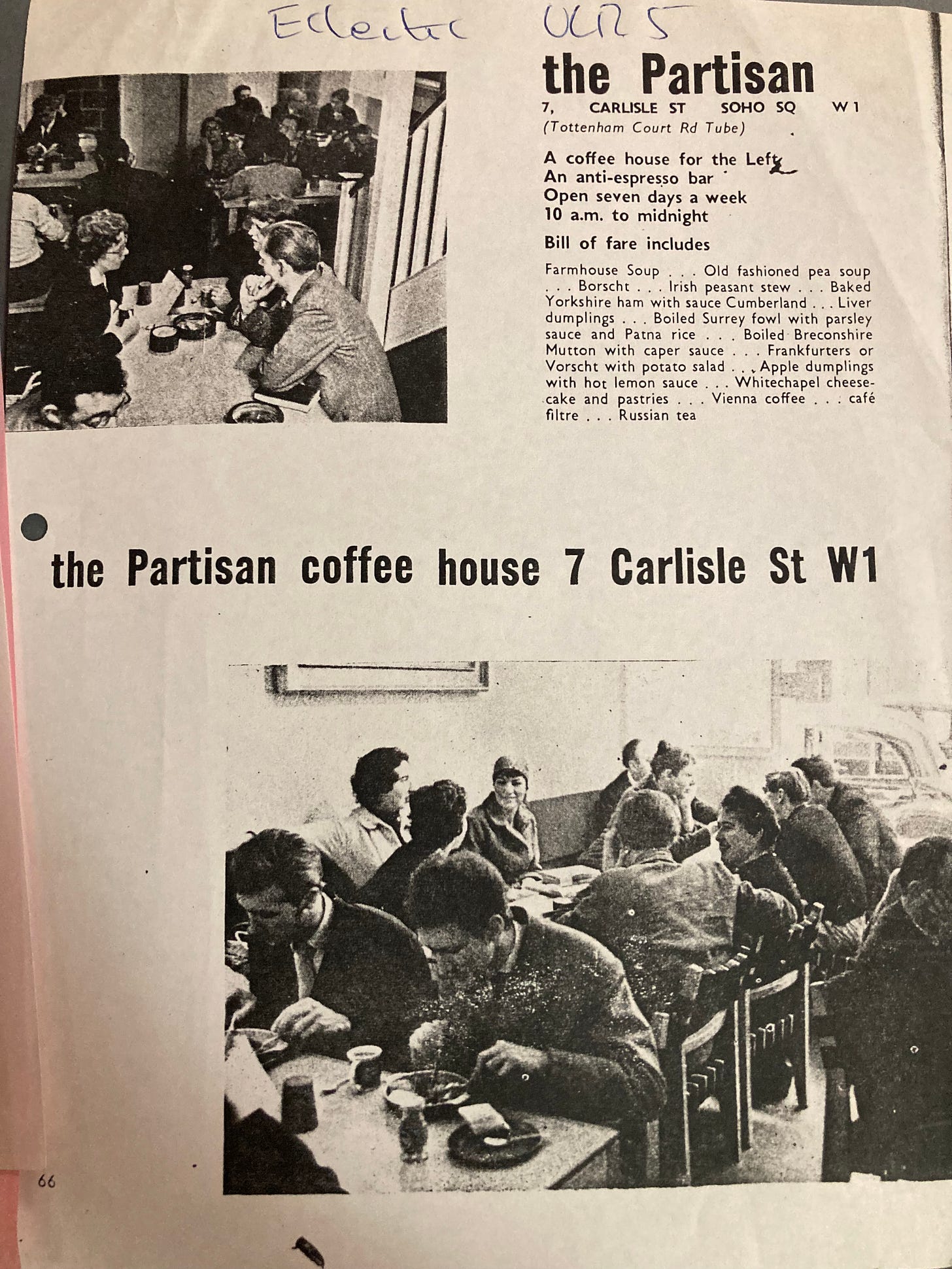

Driven by an ‘activist zeal’, Raphael was the organising force behind much of what the magazine achieved.[xii] He was also – despite the initial misgivings of his fellow editors – the primary architect of both the New Left Clubs, whose aim was to create spaces for the discussion of contemporary politics across the country, and the Partisan Coffee House, the left-wing ‘anti-espresso bar’ in Soho that first opened its doors in October 1958.

In late 1959, ULR merged with fellow socialist magazine New Reasoner to produce New Left Review. This was edited from Yorkshire by John Saville and E. P. Thompson, both former CP members. Politically, they were a generation older than the editors of ULR, and exponents of a kindred form of socialist humanism. By 1963, however, under severe financial constraint and amid mounting internal pressure, the original NLR editorial board, then led by Stuart Hall, was replaced by a new collective under Perry Anderson, a young historian fresh from Oxford. Samuel was to edit one transitional issue of the journal in early 1962, published characteristically late and over-length, in the brief hiatus between Hall’s resignation and Anderson’s appointment.

The early 1960s were something of a political caesura. Into this, many expected, or hoped, to see a new political generation emerge. Yet the cumulative effects of the political and personal crises that began in 1956 were starting to take their toll. Samuel experienced a deep crisis of confidence and, later, a near breakdown. By 1963, following a bout of political disenchantment, Samuel left Britain for Ireland where he hoped to find refuge and the freedom to write history and poetry – even hoping, he later suggested, to become Irish.[xiii]

Samuel’s stay in Ireland was a significant one. Although he found little work in Dublin, and often went hungry for lack of money, it was not a stay without reward. The research rekindled his passion for history and set the tone for much of his later work. These years also saw the germination of his particular historical and educational philosophy. This can be seen in a letter Samuel wrote to his mother at some point in 1964, not long after he returned to London from Dublin. ‘When we were students,’ Samuel writes, ‘we were terribly underground and polite, and traditional learning seemed absolutely dominant.’ What was needed, he wrote, was for this ‘academic cast of learning’ to be broken with:

Whether one looks at it in history or sociology or (astonishingly) in English literature, it shows the same ineffable signs. Always one is presented with a great screen of obfuscation, subjects approached so indirectly that it’s the critical mind at work that matters rather than the experience, or the text, itself.[xiv]

So much of his writing and his teaching was aimed at removing such a screen and approaching the material directly. His work is an attempt to uncover something of the quality of life and experience as it was lived. In the often acrimonious and painful aftermath of the first New Left was the making of Raphael Samuel the historian.

It was also around this time that the historian Sheila Rowbotham first encountered Samuel at a lecture he delivered on the famine in Ireland of the 1840s, given either shortly before he left London for Ireland or soon after this return. Rowbotham, at the time a student at St Hilda’s College, Oxford, writes that the lecture was ‘revelatory’:

The small, skinny, dark figure with a lock of black hair falling persistently over his nose had a hypnotic aspect. Raphael kept shifting papers from one great pile to another across the table and, like spectators at Wimbledon, we watched them go faster and faster as his time ran out. His talk was a devastating tour de force in which he described how belief in free trade and opportunism had combined.[xv]

The Irish working class, particularly those who made the move across the Irish Sea in the years after that devastating act of colonial violence, were to become the paradigmatic outsider for Samuel: a key figure, along with Gypsies, travellers and other plebeian ‘comers and goers’, in his historical imagination.

Some two decades later, in 1985, Samuel published an essay on ‘The Roman Catholic Church and The Irish Poor’. Based on extensive archival research conducted during the mid-1960s, the essay is a brilliant piece of historical reconstruction that takes as its object the ‘moral atmosphere characteristic of the congregations of the Irish poor in England during the second half of the nineteenth century’.[xvi] The Catholic Church in England during these years was, Samuel writes, a ‘plural church’. At one end of the social spectrum the church served the ‘well-born and the rich’, particularly with the addition of those newly recruited to the church via Edward Pusey’s Anglo-Catholic Oxford Movement. At the other, and constituting the vast bulk of the growing number of Catholics in England, were the Irish migrant poor, attracted to the towns and cities of England by the rising demand for labour as well as the economic and political ravaging of their homeland.[xvii]

The essay is as much an attempt to grasp a qualitive shift in Roman Catholicism during these years, produced by the successive waves of Irish Catholic immigration and the reaction of local Protestants, as it is to track the quantitative shift in congregations they produced. What is at stake is a social history, drawn from a diverse range of sources, whose aim is to show what a ‘merely ecclesiastical history of religion is likely to neglect’: namely, the social and moral tenor of the life of the Irish Catholic poor in Britain.[xviii] Usually housed in the poorest districts, the Catholic congregations were crammed into small chapels, often little more than dilapidated rooms or jerry-built huts set amid the dense network of lodgings that made up the new Irish quarters of towns and cities. Their schools, founded in great numbers by the Church in the later part of the century for the education of the Catholic children, were in many instances worse: one in Liverpool merely a room above a cowshed, another in Barnsley ‘only a cellar’.[xix] Nor were the clergy hidden away in more respectable and salubrious surroundings. Priests in poor neighbourhoods lived in modest dwellings in close proximity to their congregations, and their houses often served as a focal point for the community. At St Peter’s, Birmingham, in the winter of 1862–3, the priest was twice taken to remind his flock that sick calls were not to come later than 10 p.m., ‘except in very urgent cases which seldom happen as those which are called urgent are nearly always nothing of the kind’.[xx]

Many of the laity were a tough and riotous lot, ready to defend their faith with ‘something of that primitive violence which made it dangerous, in the more inflammatory parts of rural Ireland, for a bailiff to serve his writ or for a landlord to reside’.[xxi] To this, the Catholic priests attempted to introduce some Victorian respectability, often with little success. One notable figure was Father Theobald Mathew, the Capuchin friar and temperance campaigner who became the leader of the Cork Teetotal Society in 1838. He toured Ireland, making the bombastic claim in 1842 of having delivered the pledge to some five million of his countrymen, before transferring the crusade to England.[xxii] Of those who made the pledge to Father Mathew that year, many soon fell off the wagon, it being ‘less a decision for life … than an interlude of remorse between compulsive bouts of drink’.[xxiii]

Surprisingly, the essay ends with something akin to a methodological and historiographical coda. It was, Samuel writes, ‘in the summer of 1966’ that he first began to conduct the research for the essay, ‘travelling the parishes and record offices of northern England’ in search of material. The old Irish quarters of towns and cities that he encountered in those years had ‘not yet succumbed to the bulldozer and the depredations of comprehensive clearance and re-development’. The Irish Catholic churches he visited ‘often seemed to stand in half-deserted urban wastelands’, and in taking tea with the local priests (including one who sat down to dinner ‘in his tobacco-stained waistcoat’) he was able to gain access to long-forgotten documents, those scraps of paper that in the hands of a skilled historian can open new historical vistas. There is, in this essay, a palpable sense of Samuel’s passion for historical enquiry as well as his devotion to telling the stories of those outcast from respectable society.

The cast of characters it conjures forth includes Tom Barclay, recalling his Irish Catholic childhood in Leicester, and whose mother, brought up ‘in the wilds of County Mayo’, takes consolation from her difficult life in an ‘old Irish lamentation or love song and the contemplation of the sufferings of “Our Blessed Lord” and his virgin mother’. Father Vere, a Soho priest, is described chasing after the truant children from the local Catholic schools – or ‘child hunting’, as he called it in his memoirs. There is also the group of Irishmen in Ancoats, Manchester, who in 1871 filled in their census returns in the local pub, or ‘the House of Commons for Ireland’ as the local newspaper called it. We even read of the oft-remembered figure of the ‘turbulent Irishwoman, with her sleeves tucked up, and her apron full of stones’, ready to defend her patch from the sectarian attacks of the local Protestant working class.

It is this attention to the details of life that makes Samuel’s writing so thrilling to read. Yet there is a broader point as well. As Samuel wrote in a letter to his mother from a Cheshire record office:

It is often the most ordinary things which are the most difficult to rescue from oblivion, and that’s one reason why history sometimes seems to be a thing quite on its own, with its own kinds of subject and reality – revolutions, constitutions, epic heroes – which have little connection with everyday life, and therefore can’t be used as part of the evidence on which we try to work out a philosophy of life and of society. You have to work against the grain and bias of the documents to find the material. So simple a thing, I find in my work, as for example a man crossing himself, or keeping sacred pictures in his parlour – or meeting his fellows, or quarrelling, in a pub is infinitely more difficult to find than the exquisite points of political controversy and alignment; yet obviously for an understanding of the way in which people lived – of what people are – vastly more important.[xxiv]

Contained here, in condensed form, are the principles that drove Samuel’s work for the rest of his life.

Samuel’s most comprehensive survey of the Victorian outsider comes in an earlier essay, ‘Comers and Goers’, originally published in the superb 1973 H. J. Dyos and Michael Wolff volume The Victorian City, and republished here for the first time. The essay charts the ‘migrating classes’ of the late nineteenth century, a capacious group that stretches from Gypsies and travellers, trailing their caravans across the back roads of rural England, to itinerant labourers, circus folk, navvies and boatmen, country hop-pickers, urban craftsmen, and the sailors of all nations who cruised the harbours and night-time pleasure strips of great Victorian ports such as London and Cardiff. This was a group who, in nineteenth-century England, ‘played a much greater part in industrial and social life than they do today’.[xxv] Yet it was also a people who, by their very nature, left few traces in the historical record. Often their world was erased almost as soon as it was built. Their workplaces and lodging houses left behind no records, existing as they did on the fringes of legality where every written report was a potential threat, and few wrote of their own exploits. It was thus often left to the middle-class social reformers and philanthropists to document the urban and rural poor. And these sources were to be used with caution.

That Samuel recreates with such skill the world of the itinerant poor is a remarkable achievement. There were, Samuel writes, four distinct classes of comers and goers in Victorian Britain. The first were the ‘habitual wanderers’, often tramps who spent the great majority of the year sleeping rough, whether in town or country. The second were those who spent much of the year labouring in the countryside, but who kept regular winter lodgings in town. The third were ‘fair weather’ travellers who wandered during the summer season but stayed in one place the rest of the time; and fourth were those who remained in urban areas, but who made frequent trips into the country for work. These types, though, in themselves constituted no cohesive groups. Such wanderers were internally variegated, and examples of each of the four types could be found in all of the ‘wandering tribes’, as the contemporary journalist Henry Mayhew called them, of Victorian England. Each of them followed distinct rhythms, often determined by the nature of their work as well as the changing patterns of the weather. March and April saw the first movements out of the cities, with the travelling showmen leaving for the great country fairs and meets of the spring and summer, later followed by the first waves of agricultural workers and Gypsies. Summer saw a large exodus from towns and cities to the country, where ‘there was big money to be earned in the fields, for the man who was prepared to rough it, and to try his luck on tramp’ – a group that often included unemployed industrial labourers and those out on strike looking for extra income.

Also heading off ‘on the tramp’ during the summer season were navvies, nomads, hawkers, and dealers, as well as a yearly influx of Irish labourers and Italian organ-grinders and ice-cream sellers. August was the off-season for many industrial occupations, owing to the heat and the slackening of trade, which pushed many urban labourers out of the towns to try their luck elsewhere, and this was soon followed by the harvest months, work for which the nimble fingers of women and children gave them an advantage. The winter, on the other hand, saw the movement reverse, and with it the great wandering tribes returned to the city once again.

Samuel makes wonderful use of Mayhew’s reports on the lives of poor for the Morning Chronicle and his four-volume compendium of interviews and reports, London Labour and the London Poor, as well as the work of the social researcher and reformer Charles Booth and his multi-volume study, Life and Labour of the People in London. But Samuel also draws on news stories, official reports and a vast quantity of memoirs and autobiographies by labouring men and women. The picture of Victorian England in the essay is one in which ‘distinction between the nomadic life and the settled one was by no means hard and fast’; rather than being the ‘prerogative of the social outcast it is today’, itinerance was ‘a normal phase in the life of entirely respectable classes of working men.’

The end of this period, therefore, as the nineteenth century turned into the twentieth, was determined more by economic change than moral reform. The growth of labour that did not fluctuate with the seasons and the increasing mechanisation of agriculture played their part, as did the growth of trades unions. Writing from the mid-twentieth century, when the life of the wandering tribes could be imagined a distant one, Samuel wrote of his fear that such research appeared anachronistic. ‘It is not easy to imagine a time’, he writes, ‘when men slept rough in the shadows of the gas-works, the warmth of the brick-kilns, and the dark recesses of places like London Bridge; or lined up their hundreds with tin cans or basins at Ham Yard, Soho, or the midnight soup-kitchens of Whitechapel and Drury Lane.’

During the period, roughly from the mid-1960s to the end of the 1970s, Samuel’s work bore the strong and obvious influence of the discipline of social anthropology. The essay on the Catholic poor opens with a reflection on ‘the changing balance of intimacy and unease’ shared between a Soho Catholic congregation and its priest, Father Sheridan, who at the weekly meeting of St Bridget’s Confraternity recites comic stories of Irish life, designed, he admits, to excite the ‘risible qualities’ of the women. This relationship between clergy and congregation, Samuel writes, ‘social anthropology may explain’, but the historian, lacking evidence, ‘can do little more than record’. An earlier essay on the village of Headington Quarry, on the outskirts of Oxford, of which a version is published here, pushed the anthropological approach further, drawing on living memory and oral testimony to show the village community as a whole way of life.

Samuel was by no means the only historian to turn to the discipline of anthropology for inspiration. In 1963, Keith Thomas published his influential essay for Past and Present on the conjuncture of the two subjects, and in it he remarks that even thirty years earlier R. H. Tawney was calling for historians to acquaint themselves with the work of anthropologists.[xxvi] Published that same year was E. P. Thompson’s ground-breaking The Making of the English Working Class, another work hugely indebted to the field of anthropology, followed two years later by Peter Laslett’s similarly ethnographic The World We Have Lost. Each placed culture at the centre of their historical analysis, but not culture as traditionally defined to mean the great works of a civilisation. Instead, this was culture as a whole way of life encompassing everything from folklore to trades unions, rough music to sports.

Samuel’s engagement with anthropology can perhaps be traced back to an earlier period still. While editing and organising at New Left Review in the late 1950s, he worked as a researcher for sociologist Michael Young’s Institute of Community Studies, the research institute formed in 1953 to investigate post-war social change. Much of the work conducted by Young and others at the Institute had a strong ethnographic feel, an influence that can be seen clearly in Young and Peter Wilmott’s now classic study Family and Kinship in East London, first published in 1957 and based on research conducted by the Institute.[xxvii] Samuel’s work for the Institute came later, and made up the basis of two studies: the first on life in the new town of Stevenage in Hertfordshire, and a later one on adolescent boys in the working class East London area of Bethnal Green that began in 1959.[xxviii]

Both studies involved hundreds of hours of interviews with participants that aimed to get a picture of the social attitudes of those who lived in each location. Samuel initially met the work with enthusiasm. There was a humanism to this form of research that appealed to him politically and it seemed to match his vision of how society both is and should be run: the face-to-face contact with people, and the probing of personal experience from which general arguments develop. But he soon became disillusioned by the limitations of the Institute’s abstract sociological vision and the orientation of its work towards public policy. To this, anthropology, along with his own burgeoning historical research, was to prove something of an antidote.[xxix]

In later interviews with Harrison, Samuel mentions that Erving Goffman’s study of ‘total institutions’ in Asylums had made an impression on him; and Samuel’s continuing focus on the concrete and particular, or (to summon a perhaps unhelpful abstraction) the human over the system, shows a clear line of influence from such works of social and historical anthropology. A 1966 letter written to his father, Barnett Samuel, testifies to the kind of effect that the infusion of anthropology had on his work, but also to the genesis of the History Workshops from the work he was doing with his students during the same period.

Both the First and the Second Year History people are turning in first class material which they’ve dug up in their local reference libraries [over the holiday period], and this makes the History seminars really creative work; certainly it’s encouraging the first year people to see that history isn’t something you dig out of textbooks and secondary work (however scholarly) but is something which you can make for yourself if you’re ready to do the work. It is marvellous the confidence with which people read papers on what they really know and are familiar with – the historical and social character of their own community: and it serves as a very natural basis for many of the most important themes of nineteenth-century history. The sociology is also quite radically improved from the injection of anthropology and folk culture. I’ve got one excellent folk singer, a miner, who’s been admirably fusing his own interests with some of the anthropological stuff: and the seminar discussions and tutorial essays are always about real things – family, community, popular religion, social solidarity, aggression, prejudice. It also puts up lots of valuable questions to the historian.[xxx]

The letter gives a sense of not only Samuel as a teacher, but also of his work more generally. In the words of the historian Sally Alexander, an early student of Samuel’s at Ruskin, his teaching was life-changing: ‘I learnt everything from Raphael’, she writes, ‘though he scarcely “taught” so much as encouraged, engaged in conversation, led us to the libraries and archives.’[xxxi]

Although never mentioned by name, another possible influence during the mid– to late 1960s was Clifford Geertz and his method of ‘thick description’. As Robin Blackburn, his long-time editor at New Left Review, remembers, Samuel often submitted his essays with comments about how a particular paragraph ‘needs further thickening’.[xxxii] Thickening here meant the addition of further layers of reference to an already rich text, giving his writing its characteristic density of material as well as its depth and range. This approach may also have been the result of his own particular, and slightly peculiar, research method – inspired by the work of the Fabian social investigators Sidney and Beatrice Webb – in which copious notes were made on loose sheets of paper, which were then sorted, shuffled, and reshuffled to create new historical constellations.[xxxiii]

While reading Samuel’s work, it often feels as though (in his own, perhaps playful, misquotation of Blake against that most Blakean of historians, E. P. Thompson) you really can ‘hold eternity in a grain of sand’; that a close and detailed explication of the concrete can in itself yield the most culturally rich work of historical analysis.[xxxiv] Occasionally, an argument seems to spring forth unexpectedly from the thicket of references and archival material, resulting in sudden moments of illumination and clarity. At others, the argument remains elusive, hinted at beyond the wealth of information, and carried through by Samuel’s immensely lucid prose. There are often hints of that other great miniaturist, Walter Benjamin, another writer whose guide through the pathways of modernity was the outsider – the ragpicker – sifting through capitalism’s waste for the fragments of a universal otherwise hidden.

All of these influences can be seen clearly in Samuel’s work on Headington Quarry, a formerly plebeian village now mostly engulfed by Oxford’s outward expansion. The research on the village had its origins in a pedagogical exercise he developed with his students at Ruskin in the late 1960s. Long chafing at the restrictions of the history curriculum at the college, particularly its emphasis on the teaching of secondary material in the classroom at the expense of an engagement with primary documents and archival work, Samuel designed a series of short research projects for students, one of which focused on the quarry – a site with easily accessible documents relating to a common rights struggle between the community and the local authorities, as well as being on the students’ doorstep.

The work on the village began in 1969 with Samuel working alongside the first group of history diploma students at the college, including Sally Alexander, whose work concentrated on the local St Giles fair, and Alun Howkins, whose father was an Oxfordshire labourer and who introduced him to labourers, poachers and travelling showmen from the village.[xxxv]

At the start of the nineteenth century, Headington Quarry was a small, open squatters’ village on the outskirts of the city. The 1841 census records a population of just 264, which was to increase to nearly 1,500 by the turn of the twentieth century. Yet even then, Samuel writes, the village had something of the feel of a squatters’ settlement.[xxxvi] Even the topography of the village signalled its contested history. Centuries of quarrying for the Headington stone that provided building materials for the grand colleges had left the village a warren of ditches, pits and declivities. As one local described it to Samuel, in one of the many oral history interviews that make up the vast material for the two essays he wrote on Headington Quarry, the village is ‘all ’oles and alleys and ’ills, that’s what the Quarry is, all up and down’.[xxxvii] Nor was there anything like the bucolic village green with its picturesque church spire rising above the surrounding cottages. This was, and remained long into the twentieth century, a thoroughly plebeian settlement: ‘a village, a rare case’, Samuel writes, ‘where enclosure may be said never to have taken place’.[xxxviii]

The inhabitants of the Quarry were notoriously rowdy, prone to fighting and causing havoc at the feasts and fairs of neighbouring villages. The ‘Headington Quarry Roughs’, as they were known to the local newspapers, also had a reputation as poachers. ‘We used to get some saucy buggers come out of different places,’ one former resident told Samuel; ‘there was some handy blokes in this village at one time.’[xxxix] What these people must have thought of Samuel with his shock of black hair hanging across his forehead, his accent clearly signifying his place as across the Magdalen Bridge in Oxford proper, as he sat among the drinkers in the Mason’s Arms, we can only guess – but it must surely have been a strange sight.

The first fruits of this research, written up from the numerous tapes recorded with Quarry locals, many of whom Samuel found in and around the pub, came in 1972. Published in the fourth issue of the journal Oral History, ‘Headington Quarry: Recording a Labouring Community’ – included in this volume – is an engaging portrait of the village and its people.[xl] It was also one of the first pieces of historical research that Samuel published.

Between the end of the first New Left in the 1962 and the early 1970s, Samuel published little. Yet from then until the end of his life, a steady stream (later a vast flood) of writing was to see the light of day. From the 1970s, Samuel increasingly began to focus on nineteenth-century social history and the history of labour, culminating in one of the great pieces of historical research and writing of the decade: ‘Workshop of the World’. Published in History Workshop in 1977, the essay showcases to the full Raphael’s wealth of historical knowledge, backed by a huge array of footnotes – over three hundred in total, many pertaining to the most unexpected material, what Samuel calls ‘more fugitive sources’: autobiographies of working people; trade journals such as The Trade Associations of Birmingham Brick Masters and The British Clayworker; obscure historical works including the fascinating-sounding volume on The History of Chairmaking in High Wycombe; plus a few characteristic references ‘temporarily mislaid’.

Written in his habitual supple and open style, the essay has an iconoclastic intent, taking aim at the conventional view of the Industrial Revolution as represented by David Landes’s The Unbound Prometheus. According to this view, by the mid-eighteenth century the factory system with its infernal machines pumping out cartloads of commodities had come definitively to replace the old system of craft production. One of the key crossover points in marking this transition was Luddism, with the plight of the handloom weavers of the 1830s written in either a heroic or a tragic key: the defiant resistance against a new and inhuman order, or the forlorn hope of a world predestined to expire.

Against this, Samuel gathers a huge quantity of both empirical data and richly sourced qualitative material to demonstrate that the advance of capitalism in the nineteenth century was not the triumphal march of progress so often imagined, but an uneven process, internally variegated and beset throughout by the kind of workplace resistance to the imposition of technology which as often as not sets the pace of change. ‘In mid-Victorian England,’ Samuel writes, ‘there were few parts of the economy which steam power and machinery had left untouched, but fewer still where it ruled unchallenged.’[xli]

If the standard narrative of the Industrial Revolution, in which the juggernaut of ‘machinofacture’ rapidly tramples all before it, is incorrect, then what kinds of work did people actually do during this period? What we’re left with is a complex and nuanced picture of labour during these decades. In describing this, Samuel guides us through the mid-Victorian economy, taking in industries as diverse as agriculture and cheesemaking, the building trades and glassmaking, and from puddlers and shinglers in the great ironworks that produced the steam engines powering industry to the cabinet-makers whose work barely moved beyond the kind of handicraft labour that had long been dominant.

Just below the surface of this historical detail is a partly concealed methodological argument. ‘The materials for an inquiry into 19th century work,’ Samuel writes with evident excitement, ‘are inexhaustible’, and much of them were as yet untouched. One of the principal sources for the essay was the technical literature of individual trades, then as now little used by historians, ‘and it is hoped that this article may indicate something of its potentiality’. We’re also told in several places, in typical Samuel style, that the essay is merely the first in a series, with the next instalment imminent. We’re even promised that the essay is based on an ‘unwritten chapter of a half-finished book’. This wasn’t to be, and keen readers of Samuel’s work will be familiar with such promises.

What we got instead was a deeper engagement with historiography, and a renewed interest in theoretical questions. Far from being merely a narrow empiricist or antiquarian, Samuel was long interested in questions of method. Never as philosophically minded as many of those who came later and who made up the second New Left, he was nevertheless a writer for whom the abstract was always present, pressed up alongside and mingling with the particular. ‘Theory-building’, he wrote, ‘cannot be an alternative to the attempt to explain real phenomena’; but neither can historical scholarship avoid contact with abstractions, no matter how deep the historians’ ‘hostility to theory’ may go, if it is to avoid the fragmentation of its discipline.[xlii] Raphael Samuel was thus a ‘people’s historian’, but one with a very specific vision of what that could, and should, mean.

If, as he writes in his essay that traces the long arc of the term, writing people’s history often meant studies of a local and specific kind – ‘taking as its subject the region, the township or the parish’ – then that was not always so. Its roots, Samuel writes, lay in the liberal-democratic school of history that emerged in France during the Bourbon restoration, and its practitioners included François Guizot, Augustin Thierry, and François Mignet, as well as (later and in a more romantic mode) Jules Michelet. In Britain, just a few years later, similar historiographical moves began to take place. Its antecedents lay in writers such as William Cobbett and Thomas Carlyle, as well as the myriad folk ballads and myths of popular memory, but it was not until the 1860s and 1870s, with the publication of J. R. Green’s Short History of the English People, that people’s history as a self-conscious genre in Britain fully emerged.

In this sense, the roots of people’s history lie in a pre-Marxist form of writing, one that exalted the long-gone days of ‘Merrie England’ and the virtues of the common people. It is also one that in the hands of the political and intellectual right, such as in G. M. Trevelyan’s English Social History, becomes ‘devoid of struggle, devoid of ideas, but with a very strong sense of religion and of values’: ‘history with the politics left out’. In this, there is, as Samuel admits, an ‘uncomfortable’ overlap at times between its right and left-wing variants. Each shares a yearning for the vanished solidarities of the past, which modern society has destroyed, and both celebrate ‘the natural, the naïve and the spontaneous’.[xliii] If this is something that Marxists may feel uncomfortable with – and many of them have – it need not be so. People’s history, Samuel writes, ‘always represents some sort of attempt to broaden the basis of history’. It is, by definition, oppositional, even if it is conducted by those on the intellectual right, and to reject it is to reject ‘the major heritage of socialist historical work’ in Britain.[xliv]

To simply give up people’s history and exalt in the abstract is no answer to the difficult questions that Samuel’s essay raises. It served as an editorial preface to the collected proceedings of the History Workshop conference of 1979, which saw one of the more public and antagonistic clashes of the intellectual left. There, on a Saturday evening in December, gathered a crowd of hundreds packed tight in a dilapidated neoclassical church in Oxford to witness a discussion between the historian E. P. Thompson and the cultural theorists Stuart Hall and Richard Johnson over the status of theory and structuralism. Following initial remarks by the chair Stephen Yeo, Hall and Johnson presented papers that reiterated their critique of Thompson’s work, notably his earlier fierce assault on Louis Althusser published as The Poverty of Theory. There followed a blistering riposte from Thompson that shaded into personal insult. As the historian Dennis Dworkin has noted, after E. P. Thompson’s bad-tempered intervention, ‘what had begun as a debate about Althusser was transformed into a debate about Thompson’.[xlv] It is in this context that Samuel’s essay must be read, not least his concluding remark about the need for both theory and historical work in conjunction. ‘British Marxism’, he writes, with the figures of Thompson, Hall and others looming behind him, ‘is certainly in need of the kind of nourishment – or dialectical tension – which an encounter with people’s history could provide.’

What people’s history has always sought to do, and Samuel’s work is no exception, is to ‘broaden the basis of history, to enlarge its subject matter, make use of new raw materials and offer new maps of knowledge’.[xlvi] What that broadening means in practice is as varied as its practitioners.

The essays gathered here show what the outlines of such an encounter could be. The writer and thinker contained in these essays is at his most historically acute. The work offers no escape from the theoretical into the empirical, but rather shows his immense gift for holding the two in dialectical tension. To read the essays collected in this volume is to be reminded of the depth of Raphael Samuel’s historical understanding and his contribution to history and historical thinking. More than that, it is to understand the value of living memory and oral testimony. It is to see that capitalism’s rise was not the triumphal march of progress, but a bloody combined and uneven process whose messiness and meanings were shaped by the marginal, the migrant and the fugitive. It is to feel the depth of the socialist tradition in English life, rooted so often in a particularly Christian philosophy, but one which has reached out to international radical movements since the English and French revolutions and beyond; and to understand the legacies of empire entrenched in people’s minds and everyday lives everywhere. From this, I hope, both students of history and the contemporary left have much to learn.

[i] Bill Schwarz, Foreword to Raphael Samuel, Theatres of Memory, London: 2012, p. vii.

[ii] Schwarz, Foreword to Samuel, Theatres of Memory, p. 3.

[iii] Raphael Samuel, The Lost World of British Communism, London: 2006, p. 43.

[iv] LW, p. 13.

[v] LW, p. 45.

[vi] LW, p. 14.

[vii] Raphael Samuel, Workshop of the World: Essays in People’s History, London: 2023, p.tbc

[viii] LW, p. 14.

[ix] Alison Light, Preface to Samuel, Lost World of British Communism, pp. viii, ix.

[x] Brian Harrison, ‘Interview with Raphael Samuel’, 23 October 1979. Thanks to Sophie Scott-Brown for providing me with the transcript of these interviews.

[xi] Eric Hobsbawm, Interesting Times, London: 2002, p. 206; John Callaghan, Cold War, Crisis and Conflict: The CPGB 1951–68, London: 2003, p. 17

[xii] Andrew Whitehead, ‘Interview with Charles “Chuck” Taylor’, 9 February 2021, andrewwhitehead.net.

[xiii] Alison Light, email to author, 5 October 2022.

[xiv] Unpublished letter, undated. Copyright, Estate of Raphael Samuel. A selection of Samuel’s letters is currently being planned for publication.

[xv] Sheila Rowbotham, ‘Some Memories of Raphael, NLR I:221, January–February 1997, p. 128; Sheila Rowbotham, Promise of a Dream, London: 2000, p. 62.

[xvi] Samuel, Workshop of the World, p. tbc.

[xvii] See A. D. Gilbert, Religion and Society in Industrial England, London: 1976.

[xviii] Samuel, Workshop of the World, p. tbc.

[xix] Samuel, Workshop of the World, p. tbc.

[xx] Samuel, Workshop of the World, p. tbc.

[xxi] Samuel, Workshop of the World, p. tbc.

[xxii] Colm Kerrigan, ‘Mathew, Theobald (1790–1856)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: 2004.

[xxiii] Samuel, Workshop of the World, p. tbc.

[xxiv] Unpublished letter, 28 August 1966. Copyright, Estate of Raphael Samuel.

[xxv] Samuel, Workshop of the World, p. tbc.

[xxvi] Keith Thomas, ‘History and Anthropology’, Past & Present, 24:1, April 1963, pp. 3–24

[xxvii] Lise Butler, ‘Michael Young, the Institute of Community Studies, and the Politics of Kinship’, Twentieth Century British History, 26:2, 2015, pp. 203–24.

[xxviii] Sophie Scott-Brown, The Histories of Raphael Samuel: A Portrait of a People’s Historian, Canberra: 2017, p. 86. Samuel’s work on the Stevenage project has recently been studied: Jon Lawrence, Me Me Me: The Search for Community in Post-war England, Oxford: 2019.

[xxix] Interview with Brian Harrison, 1979.

[xxx] Unpublished letter, February 1966. Copyright, Estate of Raphael Samuel.

[xxxi] Poppy Sebag-Montefiore, ‘Beyond “Misbehaviour”: Sally Alexander in Conversation’, History Workshop Online, 11 March 2020.

[xxxii] Robin Blackburn, ‘Raphael Samuel: The Politics of Thick Description’, New Left Review, I:221, January–February 1997, p. 133.

[xxxiii] This method is discussed in greater detail in Alison Light, ‘A Biographical Note on the Text’, in Raphael Samuel, Island Stories: Unravelling Britain, London: 1998, pp. xix–xxi.

[xxxiv] Raphael Samuel, Introduction to Raphael Samuel (ed.), Village Life and Labour, London: 1975, p. xix.

[xxxv] Sophie Scott-Brown, The Histories of Raphael Samuel, p. 142; Sally Alexander, email to author, 9 October 2022.

[xxxvi] Raphael Samuel, ‘Quarry Roughs: Life and Labour in Headington Quarry, 1860–1920. An Essay in Oral History’, in Raphael Samuel (ed.), Village Life and Labour, London: 1975, p. 142

[xxxvii] Samuel, ‘Quarry Roughs’, p.144.

[xxxviii] Samuel, Workshop of the World, p. tbc.

[xxxix] Samuel, ‘Quarry Roughs’, p. 148.

[xl] There was also a second, much longer essay published in 1975 in the first volume in the History Workshop book series, Village Life and Labour. Unfortunately, due to space (it comes to over 55,000 words on its own) we are not able to include it here.

[xli] Samuel, Workshop of the World, p. tbc.

[xlii] Raphael Samuel, ‘History and Theory’, in Raphael Samuel (ed.), People’s History and Socialist Theory, London: 1981, pp. l, xi.

[xliii] Samuel, Workshop of the World, p. tbc.

[xliv] Samuel, Workshop of the World, p. tbc.

[xlv] Dennis Dworkin, Cultural Marxism in Postwar Britain: History, the New Left, and the Origins of Cultural Studies, Durham, NC: 1997, p. 239.

[xlvi] Samuel, Workshop of the World, p. tbc.