Anti-Communism is back in fashion. Writing in Restoration, the substack of the increasingly right-wing Clash of Civilizations activist Ayaan Hirsi Ali, one of the more prominent former leftists now gathering on the right, Nina Power, recently wrote of her conversion from Marxist academic to right-wing freethinker. What made her overcome “the progressive mindset”, with its manichaean “good person/bad person (or sometimes, oppressor/oppressed)” distinctions, she writes, was the standard set of Culture Wars grouches: cancel culture; the take over of discourse by “a pathological minority” who wish to “impose their desires and narrative on everyone else, either by physical violence, or by social and economic punishment”; the propensity for the left to call anyone they disagree with fascists.

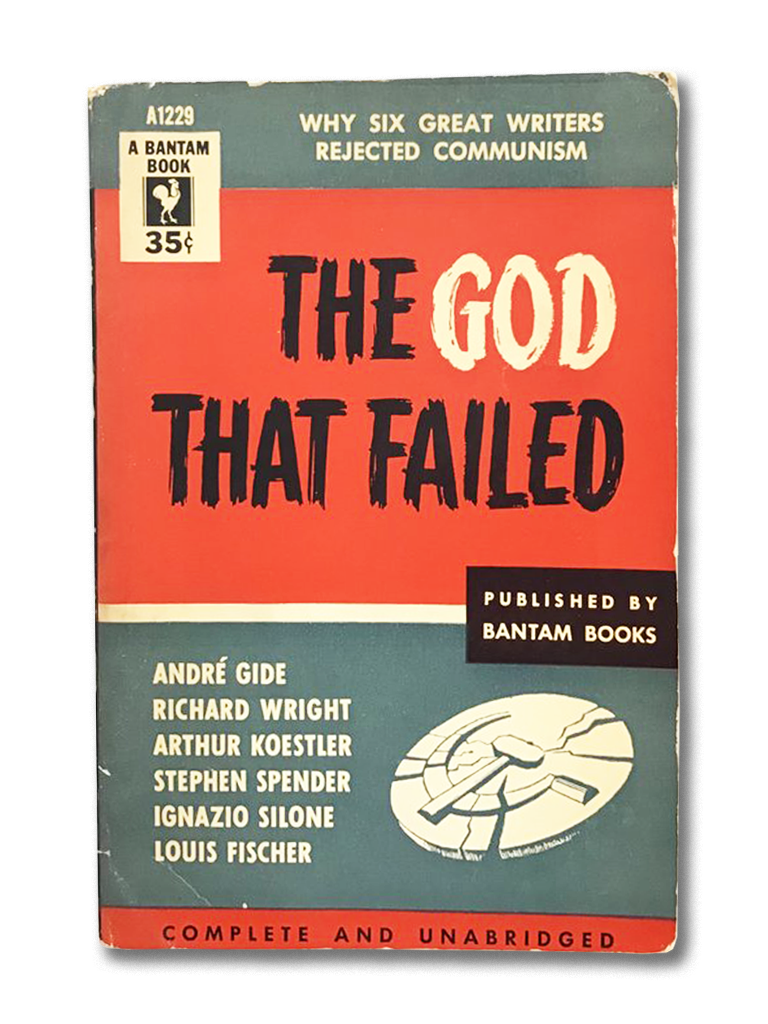

All pretty predictable, and rather dull. Less so was the reference, about half way through, to The God That Failed, the collection of essays by ex-communists and fellow travellers published in 1949, and a signal moment in the early cultural cold war. In particular, she quotes Arthur Koestler’s essay from the book (the best of the six; the others by Louis Fischer, André Gide, Ignazio Silone, Stephen Spender, and Richard Wright). Here’s how Koestler describes his conversion away Marxism:

Gradually I learned to distrust my mechanistic preoccupation with facts and to regard the world around me in the light of dialectic interpretation. It was a satisfactory and indeed blissful state; once you had assimilated the technique you were no longer disturbed by facts; they automatically took on the proper color and fell into their proper place.

“Undoubtedly something similar has happened to many who now find themselves questioning the progressive mindset,” Power writes.

Anyone who knows me will be able to see why i was struck by this. I have long been obsessed with the ex-Communists of the 1950s. I even managed to sneak The God That Failed into the Verso end of year staff picks last year. As i wrote then, reading the collection against the grain, I think it remains one of the best testaments we have to the affective mode of Communist life in the 1930s and ‘40s, when so many sensitive intellectual young men and women were drawn into Communism. What was it like to be a Communist in those pivotal decades? What did the fight for the soul of Europe, an existential struggle against the forces of Fascism, feel like to those who participated? For obvious reasons, the best guides to these questions aren’t the ones who stayed in the fold, but those who left and came to question their faith. As many a literary or cultural critic knows, the outsider is often the clearest guide.

In contrast, none of those post-leftists grumbling endlessly about cancel culture seem able to offer any clarity on what they have left behind, beyond a bunch of lazy generalisations. I think the reason for this is pretty obvious too: the contemporary left is nothing like the old left of the 1930s. For better or worse (i’d shade towards the former, overcoming whatever easy nostalgia you can have for when we had a proper left), this is a very different moment. Both the progressive and the reactionary models are different, even if it increasingly feels like we’re in some kind of early Weimar moment. And if nothing else, the form of commitment we have on the left now is incomparable to that of the high point of the Communist left. I mean, in the bluntest terms, we don’t even have proper political parties to commit to anymore. And the Stalinist purges, it should not be required to add, have nothing in common with things like losing your editing job because you decided to play act as a Nazi on the internet.

But still, references to the new threat of communism abound on the right. The aforementioned Substack of Ali lists as the number one threat to our “Judeo-Christian moral framework” a “resurgent communism”, placed even higher than “Technocratic Managerial Regime” (whatever that means), and the oh so predictable “Islamism”. For Ali, this communism “is cultural. It is firmly embedded in our core institutions. It is international in outlook, and breath-taking in its subversive ambition. And it again has traction among the young.”

Deeply unhinged stuff, i’m sure you’ll agree. But not isolated. Tucker Carlson, in his recent interview on the cretinous Red Scare podcast, decried modern “Gay Race Communism”. And as John Ganz just noted, J.D. Vance has recently blurbed a book on the “The Secret History of Communist Revolutions”, which according to the publisher’s blurb demonstrates that “We're in a new revolution right now.” Ganz also posted a link to a recent interview with Peter Thiel, where he talks about the ongoing “battle against communism”. “In some ways,” Thiel says, “my formative political idea as a teenager — junior high school, high school, late ’70s, early ’80s — was anti-communism.”

Against this, it’s instructive to read Isaac Deutscher’s incredible essay on the ex-communists from 1950. There, Deutscher compares Koestler and co. to that previous generation of revolutionaries-turned-reactions, the French Revolutionary generation. Just as “the ex-Jacobin became the prompter of the anti-Jacobin reaction in England”, Deutscher writes,

our ex-communist, for the best of reasons, does the most vicious things. He advances bravely in the front rank of every witch hunt. His blind hatred of his former ideal is leaven to contemporary conservatism. Not rarely he denounces even the mildest brand of the ‘welfare State’ as ‘legislative Bolshevism’.

He contributes heavily to the moral climate in which a modern counterpart to the English anti-Jacobin reaction is hatched.

His grotesque performance reflects the impasse in which he finds himself. The impasse is not merely his – it is part of a blind alley in which an entire generation leads an incoherent and absent-minded life.

All too familiar sounding.