Dig Where You Stand!

1

“It is not knowledge we lack. What is missing is the courage to understand what we know and draw conclusions.” So ends Sven Lindqvist’s extraordinary book Exterminate All the Brutes.

What does it mean to know, and to act? How does knowledge–of the past, of history, of ourselves–shape the present and the way that we see and understand the world?

Exterminate All the Brutes is Lindqvist’s most famous book. Part travelogue of his tour around the Francophone Sahara accompanied by an antiquated computer and stacks of floppy disks filled with research material, themselves constantly filling with Saharan sand, part deep history of the genocide conducted by white Europeans in the name of progress and civilization. The title, taken from the end of Kurtz’s report on the civilising task of the white man in Africa in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, guides the reader through the book. Who are the brutes? What lengths does humanity, do people, go to justify genocide?

2

What does it mean to know, and to act? How does knowledge, present or absent, used or misused, shape the present?

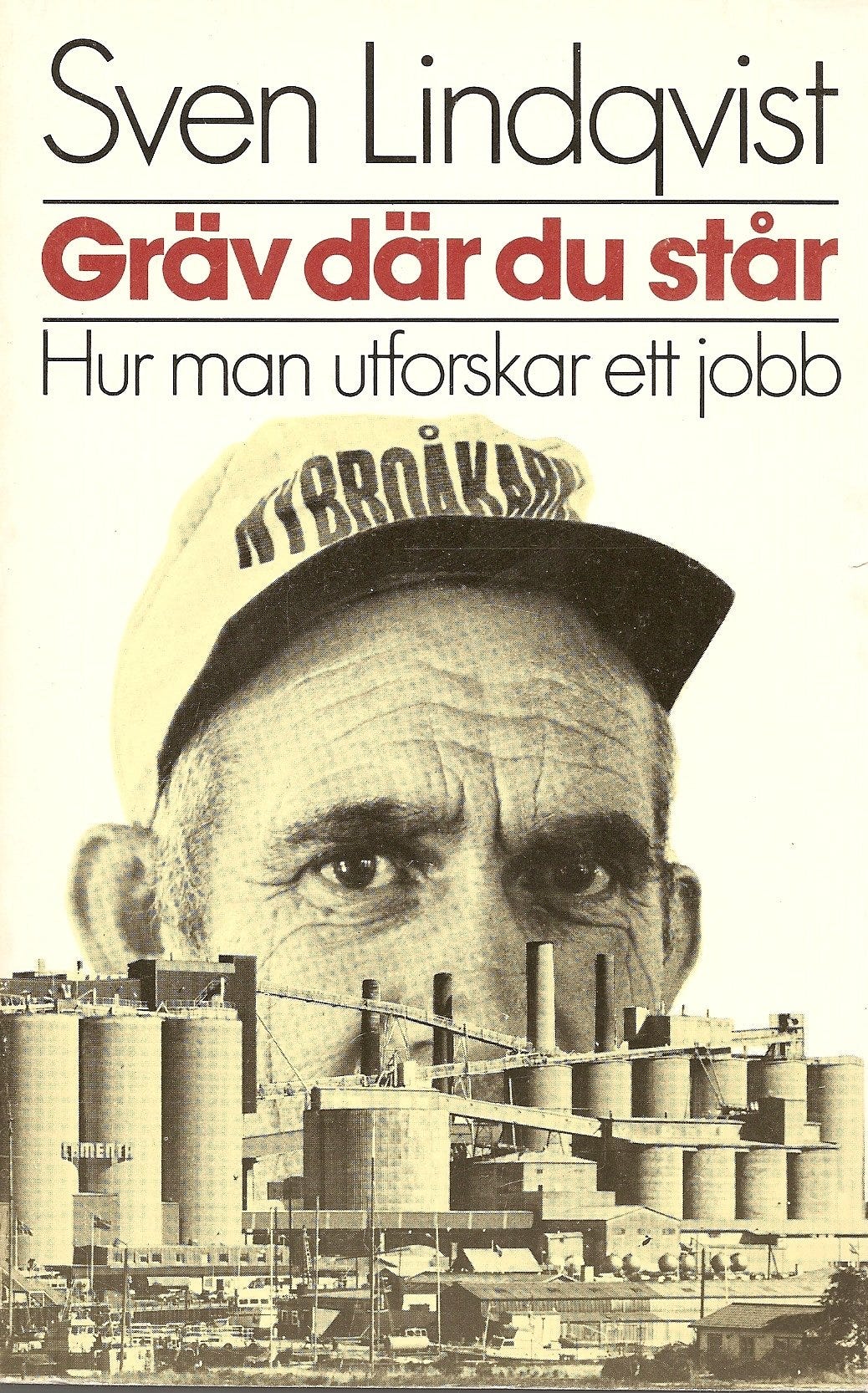

14 years before Brutes, Lindqvist published Gräv där du står. Dig Where You Stand. While the later book received wide, albeit somewhat occluded, acclaim in the English speaking world, the earlier work, over 40 years on, remains to be published in English translation.

This despite its almost immediate and wide reception not only in Sweden, but Norway, Germany, and France. In each, the book’s publication gave workers the tools to understand themselves and their histories, forging movements to “Dig Where You Stand!”

This despite the movement in British history that stretches from the Communist Party historians onwards via E.P. Thompson’s groundbreaking work of historical rescue The Making of the English Working Class.

This despite the work of Stuart Hall, Richard Hoggart, Raymond Williams.

And this despite those who gathered in and around Ruskin College and who themselves sought to give workers, ordinary women and men, the tools to understand their own history. Those who, with Raphael Samuel, founded the History Workshop movement. Who wanted to democratise historical research, to democratise history, knowledge.

3

“History is too important to be left just to professional historians.”

Of all the generation of historians who sought to write a new history from below, it was Raphael Samuel whose vision was the most thoroughly democratic. Not content with simply writing the history of workers, he wanted those same workers to have to tools to write their own histories.

Perhaps my favourite of Samuel’s texts his is essay on the Oxfordshire village of Headington Quarry, “Quarry Roughs”. This village, just a few miles outside of the city of Oxford, home of Ruskin College the trade union college where Samuel taught history for most of his academic career, had nothing particularly exceptional about it. It was typical of the “open villages” in the county of Oxfordshire, those without a great lord or squire, no rich farmer for whom all worked. It started life as a squatted village, and even into the twentieth century had avoided the enclosure of common plots that had blighted so much of England’s village life and labour. This was not, Samuel emphasises, a pre-modern remnant, but a result of the enclosure itself, and the subsequent depopulation, of closed villages, whose landlords raised rents, cut back the means of subsistence, forced villagers from there homes to produce the idyll of country life for those in the big house.

Beneath this seemingly bucolic backdrop lurks more dramatic events. Against the typical portrait of the traditional, deferential, countryside, Headington Quarry and its residents “had a very bad name”, one that was “as much because of the truculent character of their population as because of the sanitary defects widely alleged against them. Headington Quarry was a place like this, down to the Edwardian years.” The villagers were tough, plebeian. Most of the residents of the Quarry worked in the building trade, half of them producing bricks in the local yards. Their politics were strongly Liberal, and there is an accompanying shot of the Conservative party election van tipped into a roadside ditch, pushed there by local lads. Even, Samuel says, the local’s pets had a bad reputation: “there [were] complaints from the neighbouring village of Heddington about the ferocity of Quarry's dogs!”

But, the real focus of Samuel’s essay was not to dispel the myths that linger over the fields and fens of England. No, it was to make a case for oral history. The researcher can labour away for years in the archive, but what can they know of the social and moral economy, the cornerstones of life, in a village if they do not leave the archive and spend a day in the pub, talking to those who themselves took part in the brick trade, whose fathers creep out in the dead of night to poach rabbits that he would then sell door-to door?

“Historians have very often simply followed the lines suggested by the documents.” And documentary history produces documentary results. What kind of history would we get if we used different tools, different means, to look at the same events?

4

“Dig where you stand!”

The call comes from an unexpected source. Nietzsche’s poem Undaunted begins: “Where you stand, there dig deep!”

If Brutes was the story of how humans are made less than human, Dig turns the tables asking how humanity can be restored to those who would otherwise be forgotten. It’s watchword is “do not fear the expert.” Lindqvist: “when they discuss your job, you are the expert…Dig where you stand!”

5

“History is dangerous”.

For those who suffered under the fate of 19th and 20th century tyrannies, that history was dangerous was not something they needed to be reminded.

For those Tasmanians, Hottentots, or the populations of Africa, the Americas, Australia and New Zealand? Or for Europe’s Jewish populations?

While, for Arno J. Mayer and his history of the Holocaust in historical context, Why Did the Heavens Not Darken, to find antecedents for the Holocaust one must go back to the apocalyptic horrors of the Thirty Years War, or those Crusaders who stormed the city of Mainz in 1096 and murdered thousands of the city’s inhabitants. For Lindqvist, the story has a much more recent, and barbaric, beginning.

“Auschwitz was the modern industrial application of a policy of extermination on which European world domination had long since rested.”

6

Exterminate All the Brutes is not an easy read. The text is littered with the story of European-led mass murder. Thousands of people were beheaded, shot, killed where they stand. Millions of people were slaughtered to bring progress to those who stood still.

7

History remains dangerous.

“When you open the dead body you will find history in the form of silvery fibres - the last remnants of the air these people had to breathe in the factories and workers' quarters at the beginning of the century.”

The history of workers in the twentieth century is one of slow death, industrial death. It is a death that comes even when the tools to avoid it, when the knowledge of the danger, is available. The damage that asbestos fibres caused to lungs was first observed in 1907. By 1930, Britain had begun to take seriously the damage that it caused. And yet, even still, workers in the 1960s were dying from its effects. The tiny fibres lodging into there lungs in the gas mask factories of the 1940s, slowly killing them from the inside out.

8

But, history can be a weapon.

What Dig Where You Stand offers to its readers is a new way to relate to their immediate surroundings. In doing you, history can be written anew, written from below.

DIG WHERE YOU STAND!

I just learned that the first English edition of Dig Where You Stand will be released March 2023! https://www.amazon.com/Dig-Where-You-Stand-Research/dp/1914420950/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=